By Matt Hoffman, VP of Innovation at Enterprise Community Partners

The housing and community development sector is looking in the rearview mirror as it tries to tackle the affordability and opportunity challenges that face millions of Americans – and it is about to have a head-on collision with an autonomous vehicle.

As we work to address the 7-million unit housing shortage in the U.S. and enable people to live where they have access to good-paying jobs and high-quality schools, we need to look beyond the bricks and sticks, amortizations, and tax credits and start figuring out how self-driving cars and a whole suite of mobility, data, and communications-related technologies are about to transform how and where we live and the implications that will have for low-income people and communities.

The combination of technology and data applications being applied in urban environments, loosely referred to as “The Smart City,” has initiated a slew of policy and planning work in cities and regions across the country that provide an opportunity to shape an inclusive and equitable future for lower-income citizens and communities.

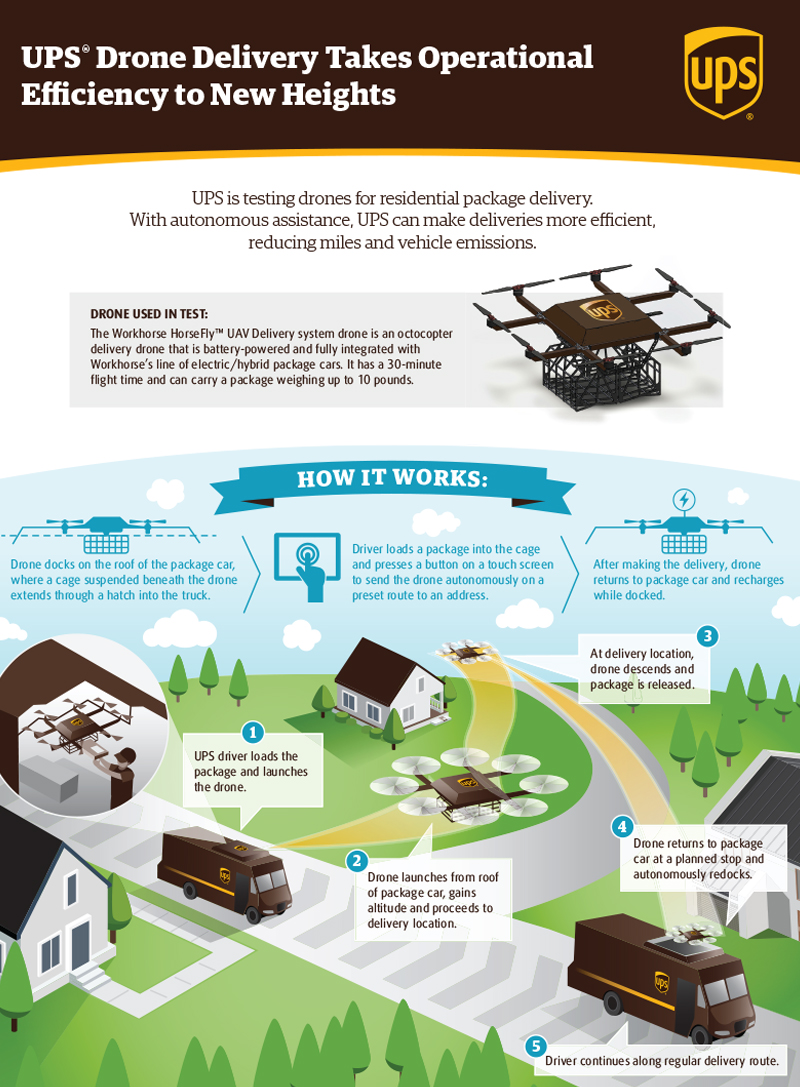

New technology-enabled forms of mobility are the biggest driver of urban transformation. Until recently, options for getting from point A to point B (too far to just walk) were limited: privately owned car, taxi, and public transportation (bus or subway). But the onset of the shared economy, enabled by digital technology and ubiquitous mobile devices and high bandwidth networks, has introduced a nascent multi-modal network that includes options such as shared private cars, e-bikes, e-scooters, shared pedal-powered bikes, and soon autonomous cars and buses.

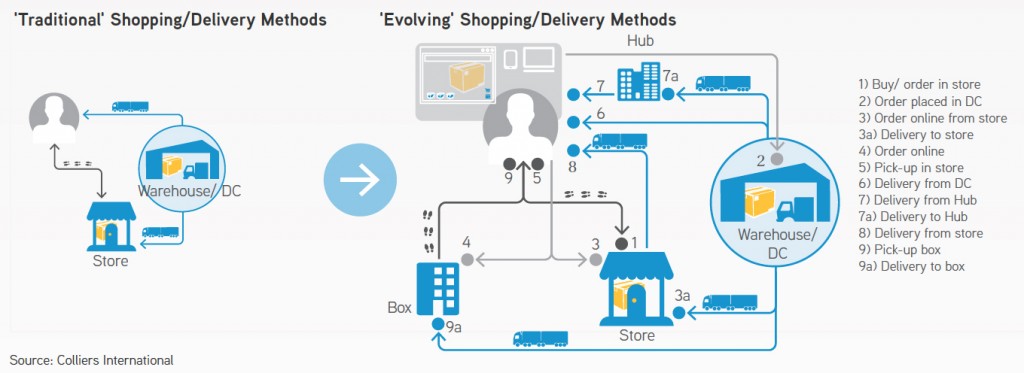

As we continue to try to build our way out of the affordability shortage, we need to do it in the context of what the market will look like over the next decade and beyond. If people can move more efficiently, at lower cost, and on-demand throughout a city, what implication does that have for how real estate is used and valued and how affordable housing is produced, preserved, and allocated? Is location in the city core or in a high-resourced neighborhood as valuable if the access or proximity to that place is not as distant or isolated as it previously was? What does transit-oriented development mean when the transit network becomes dynamic, on-demand, and comes to wherever you are?

While we don’t have a crystal ball that tells us what cities will look like 10 years from now, we do know that technology will continue to be more pervasive, less expensive to deploy, and generate some unexpected (and maybe unintended) outcomes. Identifying and applying core principles that derive greater equity, inclusion, and social and economic justice in our society will help steer us to better outcomes regardless of what technologies get deployed.

Put People First: Especially as cities plan and design transportation systems and make zoning decisions that dictate where new housing can be built and its density, these decisions must be made in the context of how people actually live and what resources they have. There has to be a balance between what we want to see and the reality of how life plays out, especially for those lacking resources. How do we help unhoused and underhoused people find permanent housing that also enables a commute to a job in less than 30 minutes? How do we help the senior citizen living alone in need of some light assistance but not appropriate for a nursing home and not able to afford an assisted living facility? How do we keep the child connected to her network of social supports where she has grown up? We must make the systems we build, both digital and analog, fit people’s lives and not build to suit the technology’s capability just because we can.

Solve Problems, Don’t Search for Them: So many technology applications seem to be solutions in search of a problem to solve. Yet the problems in the social sector are right in front of our faces: affordable housing, quality education, access to fresh food, living wage jobs, climate change, and mobility. If cities define their problems well and ask companies to bring their best solutions regardless of technology or analog function or preference, then we are likely to get better outcomes than asking for a specific technology to do X, Y, or Z. If we lead with problem-solving, then we will evolve to a city of meaning, purpose, and justice. If we lead with technology, then we are likely to end up with a dystopia.

Get the infrastructure right: Infrastructure, especially hard infrastructure that requires rights of way (roads, bridges, water/sewer, fixed rail) is extremely expensive and only gets built and rebuilt once every few generations. Decisions we make today will likely last upwards of a century. But some infrastructures, such as transportation and power are becoming more flexible and dynamic, less constrained. As cities face decisions today on critical infrastructure projects, they need to consider how needs will change over the next decades especially regarding technological and climate change influences. That means running scenarios for multiple futures and determining how any given investment will respond. It also means testing for resiliency and how infrastructure can withstand and adapt to changing climate and market conditions.

Rigorously measure outputs and assess externalities: As solutions are put in place, outputs should be measured in real time and routinely evaluated. These metrics need to be considered and structured for in advance. Assessments for externalities need to be conducted to ensure that unanticipated costs or problems are not being generated.

Open the process to citizens: Governments should view citizens as their partners, not just customers. As Smart Cities evolve and produce immense volumes of data, those data sets should be made public in real-time so citizens can help identify problems and generate solution options. Imagine the creativity and brainpower that could be unlocked if people were invited to participate in making their communities as great as possible. Rather than viewing government as something to tolerate and where citizens are essentially passive consumers of government services, rules, and regulations, we could start to shift to a partnership model where citizens felt empowered to bring solutions as well as complaints.

Let’s collectively flag down that big self-driving bus barreling down on us and hop on board. It and the other emerging Smart City technologies can help redefine what is possible for a more equitable, prosperous, just, healthy and sustainable society. It may also help us solve the housing affordability challenge.