Though no longer brand new, ridehail companies like Uber and Lyft continue to cause consternation as cities struggle with how to plan for and regulate them. Some cities have opted for trip-based taxes and fees, while others have regulated the number of cars allowed to operate. In August, New York City became the first American city to cap the number of ridehail vehicles permitted to operate each day .

Taxi drivers celebrated this move as a victory against Silicon Valley titans. But some city councilors cautioned that the New York City cap could harm low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, who have historically been underserved or avoided by taxis. Could they be right? My own research on Lyft in Los Angeles suggests: yes. Ridehailing extends reliable car access to low-income neighborhoods, majority-black neighborhoods, and areas with limited access to personal cars. A cap on ridehailing could concentrate drivers in wealthier neighborhoods, driving up prices and wait times in lower-income neighborhoods. In other words, a ridehail cap threatens to undermine the access it delivers to neighborhoods that need it the most.

Lyft serves everywhere. Data from over 6.3 million Lyft trips in Los Angeles reveal that Lyft service is remarkably ubiquitous. In a county with dense urban centers, sprawling suburbs, and remote mountain towns, Lyft trips served neighborhoods home to 99.8 percent of the population.

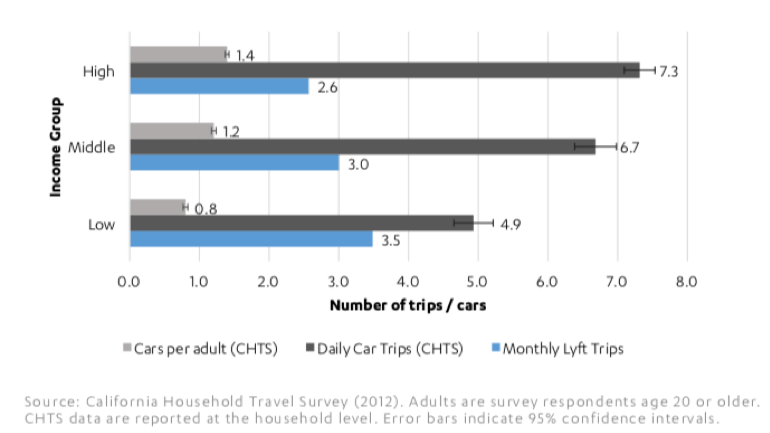

Lyft is used most where personal car access is lowest. Most people used Lyft to fill an occasional travel need, taking just one trip per month on average. But data also suggest that people took more Lyft trips where its close substitute—the household car—was scarcest and corresponding car travel was most limited.

Ridehail use is highest in low-income neighborhoods. Riders living in low-income neighborhoods relied disproportionately on Lyft, taking 36 percent more Lyft trips per month than users living in high-income neighborhoods. Riders in these neighborhoods made more of their trips on shared and less-expensive Lyft Line compared to riders living in high-income neighborhoods. Over one-third (34%) of users in low-income areas made shared trips on Lyft Line while users in high-income areas used this service less frequently, approximately 22 percent of the time. These results suggest that sharing provides an important low-cost option for cost-sensitive travelers.

Access is improved, yet questions remain, in communities of color. Taxis have historically avoided or refused to serve communities of color. Lyft presents a more promising story. Riders living in majority-black neighborhoods in Los Angeles took more Lyft trips than riders living in neighborhoods with any other racial/ethnic majority group, even after accounting for neighborhood characteristics like density and transit service. At the same time, questions about barriers to ridehail service remain. Riders living in majority-Hispanic and majority-Asian neighborhoods took fewer trips than expected all else being equal; lower use in these neighborhoods may reflect unequal banking access, smartphone ownership, or other barriers that inhibit residents from hailing a Lyft. More research is needed to ensure that all travelers can hail a ride.

Ridehailing provides car access in neighborhoods where personal access to cars is lowest. Capping the number of ridehail vehicles could encourage drivers to concentrate on higher-income neighborhoods, where they may anticipate more demand and longer, pricier trips. Taxis have long ascribed to this model, gathering around downtown hotels and businesses where they anticipate high-paying clientele. In doing so, taxis often avoid lower-income neighborhoods where personal car access is lowest, despite data showing that the residents in these areas rely disproportionately on taxis to travel by car. A ridehail cap could similarly encourage drivers to flock to wealthier neighborhoods, raising prices or wait times in less-affluent or less-central neighborhoods. Higher prices and long wait times in these communities could undermine the access benefits that ridehailing has provided to date. Worse, attempts to draw drivers into these areas through tactics such as “surge pricing”, while an incentive for drivers, could put ridehailing out of financial reach entirely for those who need it the most.

Instead of simply capping ridehailing, cities should consider the holistic role ridehailing can play in the broader mobility puzzle and how different regulations will affect cities’ visions for the future. While ridehailing can and should be regulated—such as to maintain safety standards or require data sharing—it is important that cities understand the wider effects of these regulations and implement equitable policies that will improve access for all.