While much has been said about the impact autonomous vehicles could have on the demand for parking, less has been said about what to do with the parking we have now, or what we should do with parking that has yet to be built. Parking can be split into three categories: street parking, surface lots, and parking structures. Street parking is addressed mostly through road diets in speculative pieces, and surface lots are equally easy to use as a flat, blank slate to be reinvented into something else. But what about parking structures?

Parking structures are both a challenge and an opportunity for innovative architects. They’re concrete structures with blocky columns, sloped floors, ramps between floors, irregular ceiling heights, and awkward floor plans. None of these attributes make them ideal to remodel and given the uncertainty regarding how much parking we’ll need in coming years cities may feel hesitant to take action just yet.

However, this is not a ubiquitous opinion. A few cities have been recognized for plans to turn parking lots into other uses; while not as difficult to do as parking structures, it demonstrates that cities aren’t thinking they need as much parking as they have on hand. Eventually, more articles will be written about converting parking structures into affordable housing, office space, or other uses. Here is an example of a proposed parking garage in Seattle that is convertible to residential space. For existing parking structures, remodeling their husk into a new use could be difficult and expensive, but not impossible. Here is an example of a difficult space – an abandoned subway restroom – being turned into a home by a British architect, and here a very skinny corner parcel in Japan was turned into an apartment building. These are not spaces that are considered prime real estate for redevelopment; they are not large spaces, they have funky shapes to work with, and most people would consider it a difficult endeavor to convert the space to something new and useful. But, if we can build apartments in geometrically restrictive triangles and dilapidated public restrooms, surely a rectangular, multi-story building in the heart of downtown shouldn’t be an insurmountable challenge?

Designing new parking structures poses different challenges and opportunities. Some cities are eliminating parking, but others are continuing to face a parking deficit that they don’t think autonomous vehicles will arrive in time to fix, or, that autonomous vehicles will still need lots of space to park (even if the cars are able to park closer together and line up headlights-to-taillights). Though the design of AVs is not completely clear, we know a few ways that parking garages could be more compact because of them. AV-ready garages could be re-designed:

- Parking spaces could be narrower, since passengers are likely to be dropped off at their destination and never set foot in the parking garage itself, cars won’t need the space to open doors. Aisles could be narrower as well because AVs drive more precisely.

- Parking spaces and aisles will likely both change sizes to reflect the size of vehicles, which might be stratified into a floor for traditional looking cars (personal use) or for rectangular shuttles (transit storage).

- Parking garages could use charging capabilities, and could possibly incorporate car wash stations.

- Loading lines could maximize efficiency and eliminate aisles. Assuming all cars in a garage are automated, instead of the traditional layout of singular rows with aisles in-between, loading lines without space between cars or aisles could be used for maximum efficiency (this would work for shared cars in which the car at the front of the line can be deployed for any rider).

Graphic Source: Designing parking facilities for autonomous vehicles by Mehdi Nourinejada, Sina Bahrami, Matthew J. Roorda

The previously listed considerations account for changes in technology, but not for changes in parking demand. Parking structures should be retrofitted to non-parking uses as demand for parking decreases; turning the more opportune floors of a structure (street level for connectivity, or higher stories for better lighting or views) to people-related uses, like this. To do so, new parking garages need to be re-designed to:

- reduce the number of columns, and space them so they don’t disrupt the living room that may inhabit the space in future

- use flat floors

- eliminate ramps, or use ramps that are easily integrated into a floor plan;

- Increase ceiling heights to make room for insulation, drywall, and the other building necessities of interior design without becoming too short for comfort;

- Plan with the future floor plans of housing or office space in mind;

- Allow for natural lighting. The cars won’t appreciate it, but future tenants will. A concept can be found here.

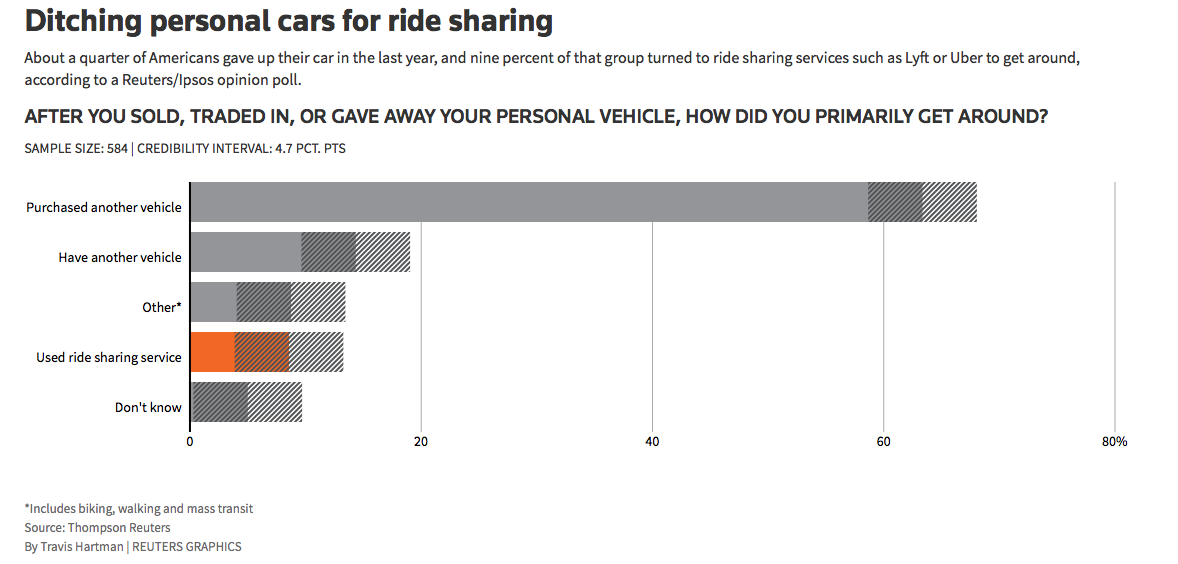

Although autonomous vehicles aren’t here yet, widespread adoption of ride-hailing services has already seen to decreased revenues for parking lots and garages. Parking lots are being bought and repurposed by developers in large quantities. Green Street Advisors, a California based real estate research firm, projects that parking needs in the US will be cut in half over the next 30 years due to a combination of ride-hailing and autonomous vehicles. It’s time to make plans for our changing parking needs, both from the effects we’re seeing today and the effects we’ll experience soon.

Jenna Whitney is a Master’s Candidate in Community and Regional Planning and an Urbanism Next Fellow at the University of Oregon. She is examining how cities are planning for a multimodal future in the era of autonomous vehicles.