We have been asked numerous times about how the introduction of AVs (and E-commerce) might affect streets. As cities make plans for future expansions, changes to their street network, the inclusion of various modes/complete streets, and overall street design – what should they be considering when they include thinking about AVs?

Here is a short list:

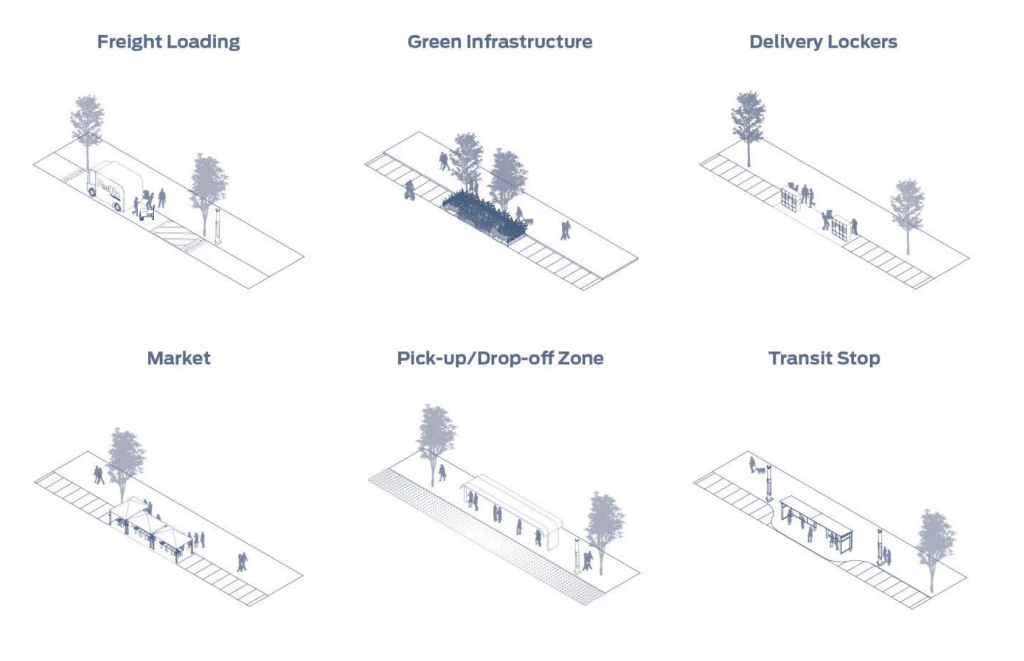

Curbside space allocation for pick-up and drop-off – This will become a large issue as demand for this space will increase substantially – especially at peak travel times. It could also cause significant disruption to transit and bike networks as AVs compete for curbside access and cut across bike and transit lanes.

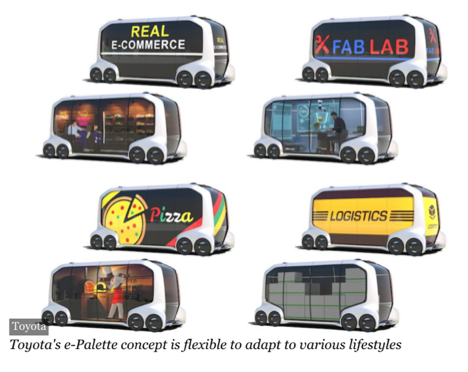

E-Commerce Delivery – Similar to above, as e-commerce expands, there will demand for curb space and places to temporarily park vehicles as deliveries are made. In addition, we will probably be seeing a large increase in delivery vehicles (an expansion of a specific kind of freight) which will affect streets and corridors?

Separation of Modes – As AVs have algorithms that don’t allow them to hit people (a fantastic development), a corollary will be that anyone walking or biking in the street can cause mass disruptions to the transportation network. A “critical mass ride” of one. This had led to calls for stronger separation between modes – a disastrous proposal – imagine our streets starting to look like China’s where there are fences between modes.

Drones on Streets – Not the flying kind (those are probably further off in the future) but the terrestrial ones. Picture an Amazon truck parking in a neighborhood and sending off twenty delivery AV rovers. Will those drive in the street? On the sidewalk? How will they affect other modes? What should we suggest or try to regulate?

Micro Transit Corridors – Lyft and Uber are pushing shared rides (Lyft-Line and Uber Pool) and are already incentivizing people to make their pick-up and drop-offs happen along arterials or more heavily travelled routes to reduce the vehicles efficiency (see this earlier post). This will define micro-transit routes throughout the city. Where will these be? Should cities help define the routes? How will it affect all modes moving through these areas?

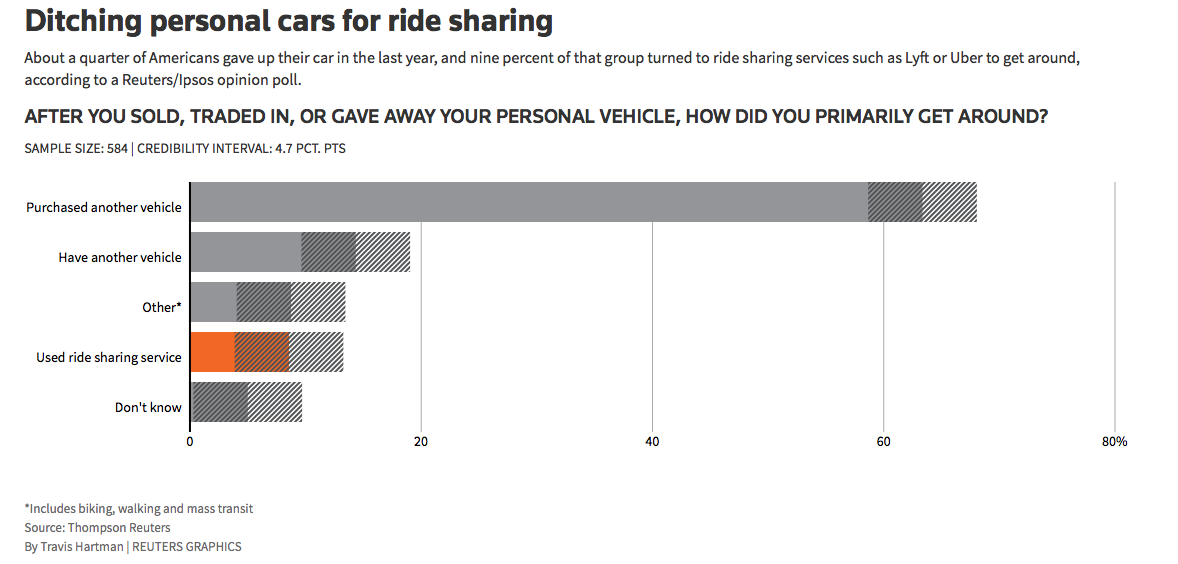

Reduction/Elimination of Parking – We are already seeing a reduction of parking use in some venues as Lyft and Uber takeoff (see this earlier post, and this one). As this happens more and more – research says we will need 10-15% of current parking spaces – what happens to the onstreet parking? Is it transferred to other modes or additional lanes? What happens to the buffering role it currently plays in many streets?

Changes to Available ROW – Building on this last point, if AVs need narrower lanes (they are better drivers than we are) and potentially can increase throughput through some streets (see point on this below) and therefore allow a reduction in necessary lanes – how will we use the available ROW. This is especially critical as available ROW seems to be one of the larger limitations to increasing dedicated infrastructure for transit, bikes, and pedestrians.

Increase in VMT – Most modeling of AVs we have seen show an increase in VMT, but this is more dramatic in scenarios where we all have our own vehicles vs shared fleets. This is especially so if we don’t tax empty cars (zombie cars) driving around as they wait for their owner or go do errands on their own. How will this increased VMT affect other modes, congestion, etc? How can we make sure we limit it?

Efficiency of Streets (for cars) – AVs in theory will be more efficient, require less space and be able to move faster. Many models have been created that show connected vehicles zooming towards each other at intersections and just barely missing as they efficiently move people and goods. What this fails to recognize is that one of the larger impediments to this type of free-flow movement is the fact that multiple users exist in the right-of-way. Pedestrians and bikes would not work well in these scenarios. This leads to thinking that there may be two worlds of cars on streets – those where they dominate (definitely freeways, but will that also start including arterials and collectors…) with free flow of vehicles and other areas where other modes are considered as well. Will the mixing of modes be frowned upon because it is such a limitation to this efficiency? Will some areas ban bikes/peds?

Street as a Utility – This is more of a meta-concept, but the idea is that we need to stop thinking of the street as a public space that we can all use whenever and however we want, but instead should think of it as a utility that has limited capacity. Related to how we pay for the amount and time of our electricity use (in places), we can think of streets similarly. This might lead to something like a geometry tax (you are charged for how much space you take up on the roadway divided by the number of people in the vehicle – a great deterrent to zombie cars). — Stay tuned for an upcoming post focused on this topic!

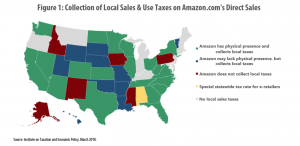

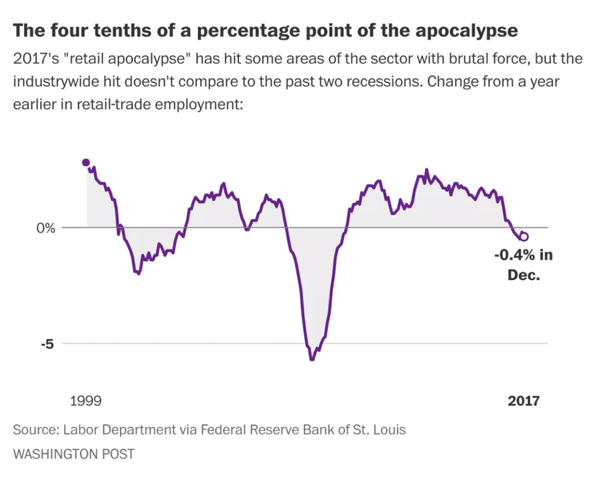

Finance – We have done a quick pass at how these technologies will be affecting municipal revenues and – in short – it will not be pretty or easy (see our report here and see analysis of parking/car related revenue impacts here). A lot of disruption (for example the drastic reduction of parking fees and traffic tickets while we are needing to pay for retraining large groups of the population who used to work in retail or driving jobs). Limited budgets will affect everything else government tries to do and services it provides – streets included.